Back in 1993, I had a dream that I was struck by a mysterious illness that led me to progressively lose my eyesight. I was eleven at the time, and in the dream, I was trying to read a book. The illness first made it difficult for me to recognize specific letters. Words and sentences soon faded out, and later, entire paragraphs slowly became blank. I tried to adapt to my condition by reading without seeing the letters g and d, struggling to understand unraveling phrases only to be faced with more disappearances here and there in the text. The sense of loss I had in the dream was not caused by my inability to read, as much as by the temporality of the condition itself: a gradually transient but recurrent state that incrementally wrecked my love of reading, and that—once I had learned to live with the damage it has caused—incited new ones.

I was a 'post-civil war kid' at that time, barely beginning to trust the outside world, and its promise of permanent safety. I had figured out how to put an end to my sleepwalking episodes and night terrors by hiding my anxieties and fears, the same way grownups would sweep weapons, bodies, and massacres under many rugs. I had also began writing my first novel نبوءة تتحقق (A Prophecy Comes True). The story narrated the prophetic birth of a girl who, through magical powers and following a series of extraordinary challenges in her life, manages to rebuild her city Beirut into a fun and lighthearted place. After the dream, however, something held me back from writing. What felt like an effortless, playful, and immensely voracious activity, became somewhat of a heavy burden, and I found myself unable to write past the first part of my novel. It was as if the condition I had in the dream was itself the prophecy of ruin to come, and of my inability to bear witness to it and adapt.

This was my first experience with interrupted writing, what is usually called writer’s block. All that remains from my novel today are several notebooks with introductory passages written on their first pages, the promise of a prophetic story without an ending:

كان يا مكان في قديم الزمان زوجان عجوزان يعيشان في كوخ صغير في الغابة

وفي يوم من الأيام أتت ساحرة و قالت

ستنجبان بنتا وستكون

خارقة الذكاء

متقدة العينين

لديها قوى خارقة

ستجوب

شوارع المدينة

وتخلق المستحيل

وتحقق النبوءة

Writing from and in various landscapes of violence is never an easy task. While most efforts go towards overcoming the block, the state of the interruption itself can emerge as a productive and generative set of affect and knowledge-ethics about the world we live in.1 In other words, perhaps we should not overcome the block and just sit with its excruciating, and sometimes repetitive, interruptions. For some, writing in-itself becomes an urgent path to overcoming violence, and when one knows they won’t be able to survive, a way to document the experience of dying. I read Jabbour Douaihy’s last novel, سمّ في الهواء (Poison in the Air),2 as a practice of writing in death and dying, where the narrator aimlessly dwells in spaces outside the margins of social institutions in Lebanon. Anthropologist Robert F. Murphy’s quasi-autoethnographic text, The Body Silent,3 documents his own deteriorating spinal condition that later led to paraplegia—a form of paralysis—his recordings countering the slowly growing silence of his body. Others prefer to sit with that violent silence, staring in awe at their world as it falls apart. When I think of being a silent observer in the face of catastrophe, a video comes to mind of a man at the beach in Thailand in 2005, staring at the tsunami as it is about to crash onto him. Someone turned the video into a GIF, and this moment now circulates online in an everlasting loop.

*

On July 20, 2024, on the eve of her fifteenth birthday, Lauren Olamina started chronicling the events unfolding with her family and small community in South California, amidst climate change, resource scarcity, and severed social relations. Lauren first wrote about random occurrences in passing—her dreams, and how her feelings for the community priest, her father, and religion were changing—while scattered ruptures in the outside world would leak into her gated community: the day she saw headless homeless people; the naked and dazed young woman she encountered in the street; the abandoned houses; the rise of political extremism in American elections; the fires, rain, tornados, epidemics, and floods; and the increasing robberies, rapes, suicides, and murders in her community.

Lauren records all this multi-leveled and episodic disintegration in an obsessive and uncannily cold manner, almost like a scientist classifying different animal species. She is a Black American teenage girl who is well versed in living-in and adapting-to a world of perpetual violence, mistrust, and socio-environmental collapse. Yet, two things were unique about Lauren: For one, her hyperempathy syndrome, otherwise known as “organic delusional syndrome,” a condition that makes her share and completely feel the pain and pleasure of other people as if it was her own, rendering her most vulnerable in times of conflict—“I’m supposed to share pleasure and pain, but there isn’t much pleasure around these days.”

The other unique attribute of Lauren is that she writes because she knows she lives on the threshold of the apocalypse, and wants to respond to its immense social and ecological changes. While her parents had lived in the 'old and more solid world,' Lauren has only witnessed and learned to live in a collapsing fragile world. Unlike the others in her community hiding and waiting for the old days to return, she had been preparing for the catastrophic moment to strike and for the walls to fall. Much to her family’s dismay, she had assembled a grab-and-run pack and had been secretly studying “three books on survival in the wilderness, three on guns and shooting, two each on handling medical emergencies, California native and naturalized plants and their uses, and basic living: logcabin-building, livestock raising, plant cultivation, soap making.” So, when the walls finally fell in a fire accompanied by a massacre of her community and family, Lauren found herself alone on the open road, in the terrifying outside. Violently uprooted, she travels with her survival pack and books, and continues to write what starts to take shape as a philosophy of change and rebuilding a new world in the aftermath of catastrophe.

*

Lauren Olamina was the protagonist of Parable of the Sower, the 1993 Afrofuturist novel on life in the apocalypse by Octavia Butler.4 I came across the novel in the summer of 2015 when I was writing my dissertation on trauma, violence, and the politics of suffering, at the break of what was later called the garbage crisis in Lebanon. My feminist community in Beirut had asked me to bring copies of her novels from the US. Intrigued, and unaware of who Octavia Butler was, I started reading the novel on my flight to Beirut. Unbeknownst to me, the day of my arrival was the day the Lebanese army opened fire on a peaceful protest in central Beirut, igniting several protests that would last for several months. Jetlagged and pumped with adrenaline, I would return home from the protests every night and read the novel.

This was the frame of mind in which I encountered Lauren. It wasn’t until much later that her diary sank in as a roadmap for survival and a guide on how to rebuild a future. What I found particularly unsettling was its absence of any portrayal of traumatic emotions and sentiment caused by violence and disaster. Despite Lauren having lost her family, community and entire world, Butler seemed adamantly uninterested in dwelling on the massacre and loss. Instead, Lauren pragmatically walks down the California highway, collecting tools for survival, still writing and journaling as a strategy for survival in a shattered world.

But what about Lauren’s suffering? The twentieth century has been preoccupied with the politics of the wound and its various subjects, identities, and retributions. This form of politics became more institutionalized by the end of the 2000s, where trauma, the universally shared wound, became a framework through which suffering produced by violence is made legible and recognizable. Trauma postulates suffering subjects, and when these subjects are not suffering from violence, they are trauma’s binary opposite: resilience. In Lebanon, my research has focused on unraveling the infrastructures of suffering from political violence and Israeli wars to explore how different economic and techno-political discourses and assemblages enable and constitute articulations of trauma and sumud (a subject position of resistance and steadfastness that is irreducible to resilience, yet contains many of its features).

How we suffer in Lebanon, whether in terms of trauma or sumud, is a very political matter. To borrow from Herta Müller’s framing,5 the sectarian-communal nerve runs deep into the land and calls for “شدّ العصب” (to stretch the nerve), serving to constitute steadfast and non-suffering, non-collapsing subjects who carry the status quo. The Beirut port explosion not only blasted the city, but tore open the infrastructures behind the discourse of resilience, emptying it of meaning and privileging trauma as a position of witnessing violence and calling for justice.

*

Yet, is trauma still the critical and urgent concept through which we can think about and recover from the violence we live in? Does it capture our affective experiences today? To put it differently: what happens when we privilege healing and rebuilding over suffering? In my work I have argued that we move away from the trauma/resilience binary towards writing about, accounting for, and theorizing on various acts, tools, and strategies for survival.6 It is a move that invites more attention and knowledge production around embodied acts of walking, cooking, planting, eating, making communities, reading violence in everyday life, and adapting. I see Lauren as an embodiment of this survivalist subject. She is neither traumatized nor resilient, because she is not preoccupied by the event of violence in and of itself. She does not stand in the face of violence, write about it, or stare in awe at its effects—but adapts to the new world that it has produced. This is not because she is apathetic from her hyperempathy. On the contrary, her abundant emotions—of empathy, pain, and pleasure—are actively and purposefully employed in the service of survival and communal rebuilding.

This is the kind of witnessing that Butler invites us to undertake in apocalyptic times, when the world-as-we-know-it ceases to be safe, familiar, and knowable. Octavia Butler inspired my thinking on how to be flexible in, mend with, and survive from catastrophe—all of this within the temporality of the everyday—how to change and transform, rather than attend to the aftermath of events. This privileging of doing rather than suffering opens our critique to generative and material ways of reading violence and disaster. It shifts focus on the future rather than the past–present. But also, Butler says, “to survive, let the past teach you.”7 The past becomes not just a painful and traumatizing event that requires healing, but also a place for deep communal knowledge, learning, and resources that we can use.

The move from suffering to doing is not an invitation to abandon the emotional and focus on the behavioral (thereby creating new binaries). It is about attending to a new kind of affective belonging in a collapsing-world, of inhabiting the threshold of the apocalypse, a kind of “apocalyptic empathy”8—a radical form of affect directed towards rebuilding, survival, and recovery.

*

I am much older now—in fact, I am about to turn forty. I have written and completed many texts. Sometimes I intentionally leave typos in them so that I can watch my writing break a little. I have had my share of interrupted writing since my first unfinished novel, and I still take prophecies seriously, even though they stopped manifesting in my dreams. Three weeks after the Beirut port explosion, I came back to Lebanon. When I called my mother to check up on her, she said our apartment was the only one in the building whose windows did not shatter. She said it was because the civil war had taught her to always leave the windows cracked open. When I came back, I was astounded to see that, contrary to what my mom said, nothing looked the same. Dust creeped into our closets and mattresses. The rooms suddenly looked worn out, kitchen cabinets seemed as if they were violently snapped and put back together. My parents, friends, and neighbors all looked incredibly old. It was like returning to a dwindling world, or to an altogether new one composed of ruins, dust, and blasted infrastructures. Inhabiting is not the same as returning, however, and the world might seem different from each position. All I know is that adapting to this new world, rebuilding communities, and recovering, extends far beyond how we have deeply suffered from it.

[1] Sitting with interruptions is inspired by the concept of the “overbearing conditions of the field” coined by the Ethnography as Knowledge working group of which I am a member. Overbearing conditions invite forms of writing on the hardships and conditions faced in research rather than overcoming them (See: Contemporary Levant 2, no. 1 (2017); and the Ethnographic Diaries project organized by Muzna Al-Masri and Michelle Obeid, to be published by Rusted Radishes).

[2] .(جبور الدويهي، سمّ في الهواء (بيروت: دار الساقي، ٢٠٢١

[3] Robert F. Murphy, The Body Silent: The Different World of the Disabled (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987).

[4] Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower Vol. 1 (New York: Open Road Media, 2012).

[5] Herta Müller, The Fox was Ever the Hunter (London: Portobello Books, 2016).

[6] Lamia Moghnieh, "Infrastructures of Suffering: Trauma, Sumud and the Politics of Violence and Aid in Lebanon," Medicine Anthropology Theory 8, no. 1 (2021): 1-26; Ibid., "‘The violence we live in’: reading and experiencing violence in the field," Contemporary Levant 2, no. 1 (2017): 24-36.

[7] Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Talents Vol. 2 (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1998).

[8] Rebecca Wanzo, “Apocalyptic Empathy: A “Parable” of Postmodern Sentimentality,” Obsidian III (2005): 72-86.

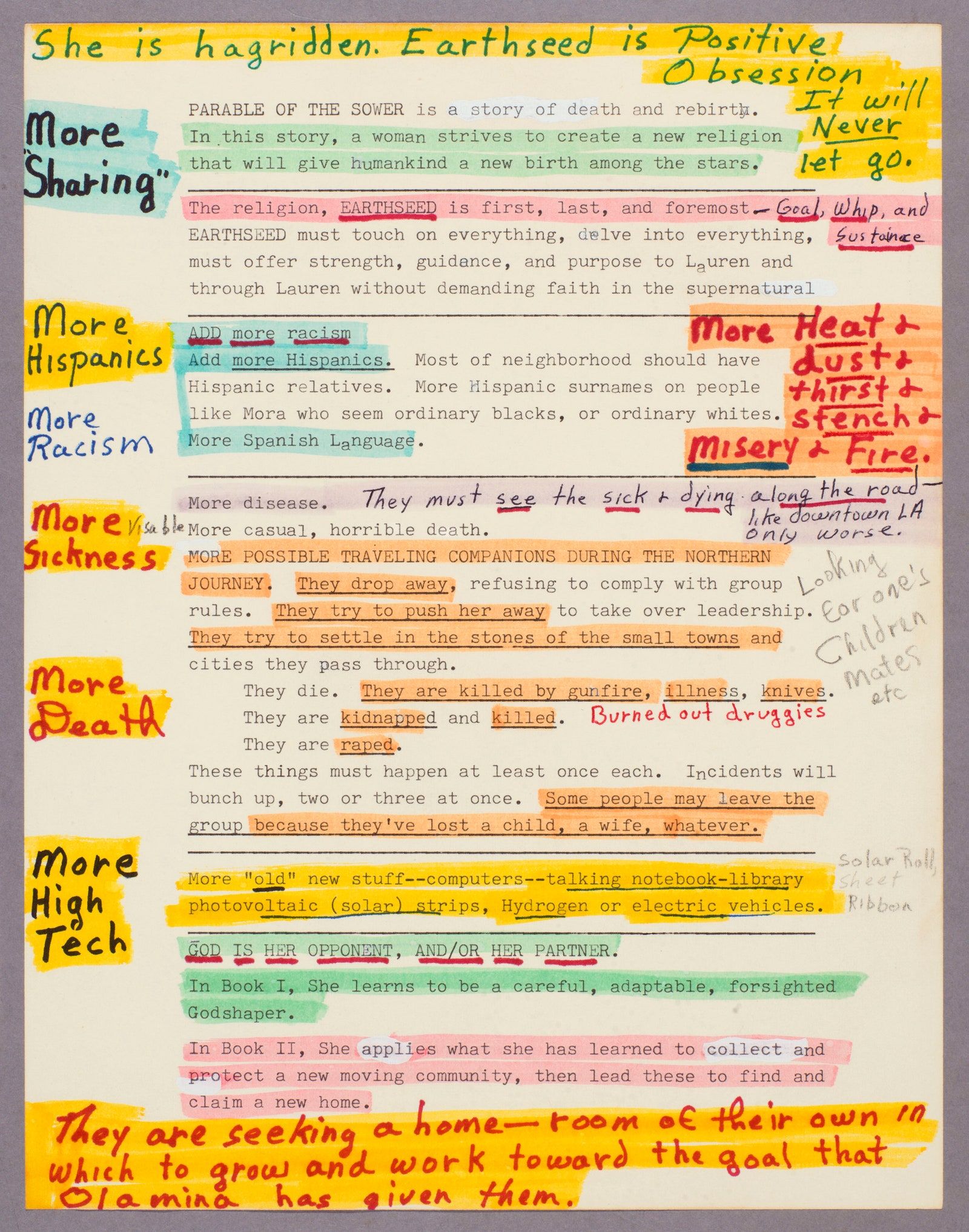

Image source: Outline and notes for Parable of the Sower, ca. 1989. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Copyright Estate of Octavia E. Butler.

Lamia Moghnieh is an anthropologist and mental health practitioner. She received her PhD in Social Work and Anthropology from the University of Michigan and is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Decolonizing Madness project at the University of Copenhagen. Her research explores the dynamics of psychiatry, suffering and patient narratives in Lebanese society and the MENA region.

This essay was commissioned with the generous support of Goethe-Institut Lebanon.