For the victims of racial violence, gun violence, state violence, and the families that endure.

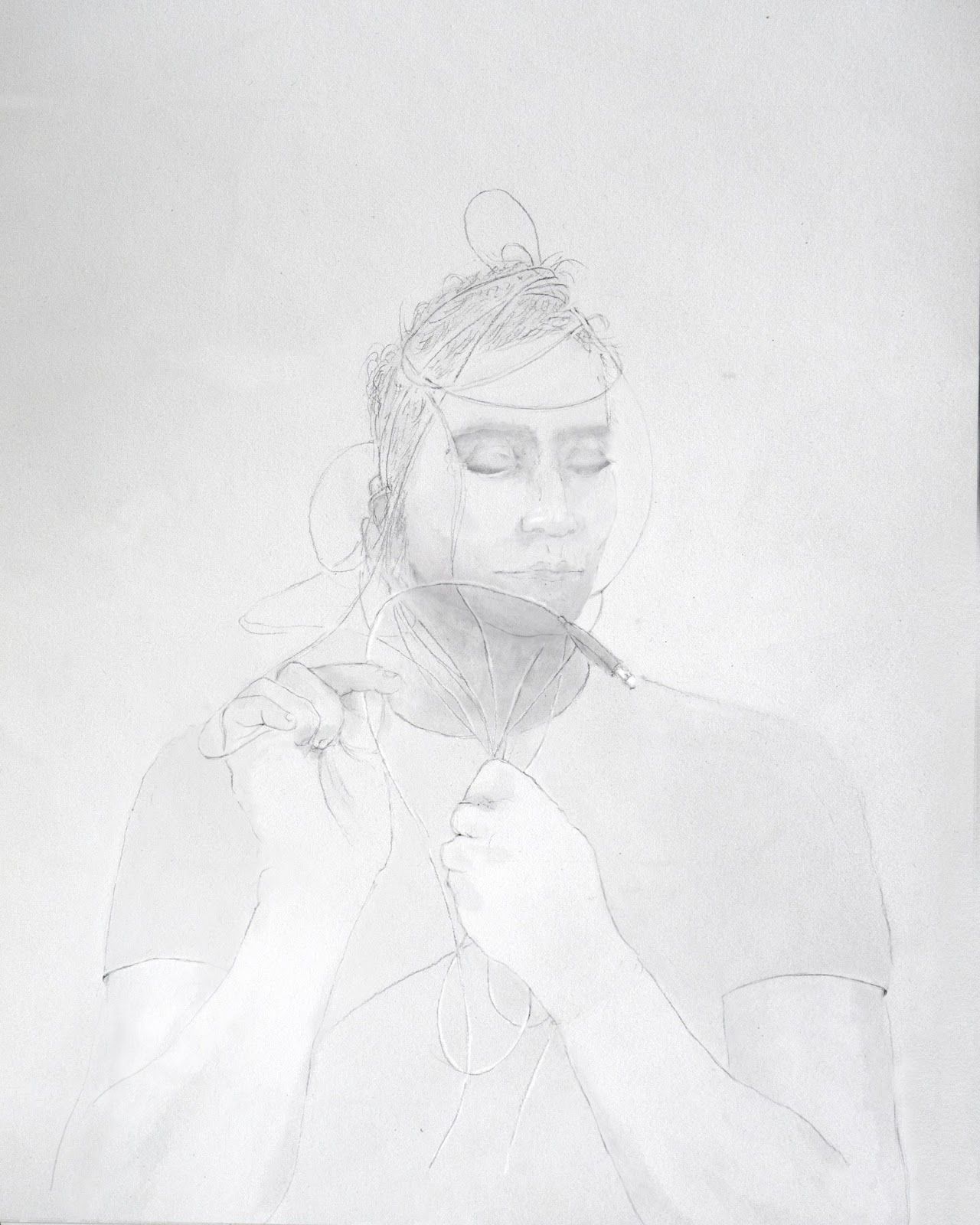

The charcoal drawing above is based on one of my favorite pictures, that of my cousin Khalid carefully and elaborately tangled in a mess of USB wires. He loved computers, especially the process of building, rebuilding, and endlessly tweaking every component and accessory of their hardware. To this day, whenever I see tangled computer cables, it makes me think of him, an everyday occurrence since his life was taken.

Khalid Jabara was murdered on the doorsteps of his family’s home on August 12, 2016 in Tulsa Oklahoma, the victim of a hate crime. Khalid was Lebanese American, South Lebanon Orthodox, and had always been the most handsome cousin; his skin was darker, with a deep chiseled jawline, doughy almond eyes, athletic build, and cousin could sing too. He lived with his parents while helping run the family catering business and caring for his terminally-ill father.

For years, the racist neighbor hurled racial slurs at Khalid and his family, projecting Islamaphobic and xenophobic slurs that didn’t even make sense. But his parents had an accent, they were different enough to hate and to not be taken seriously by the police. Over time, the slurs became increasingly more belligerent and violent, reflective of the heightened tensions instigated by the Make America Great Again rhetoric of Trump’s election campaign.

This was one of the challenges of living in a hostile environment where just being makes you suspect, less than, a threat. We instinctively knew this growing up, assimilation 101. His family was uprooted from Beirut at the height of the civil war, and settled in Tulsa in the mid 1980s. Khalid immersed himself in computers and music as a way to fit in, and be seen. In chatrooms, he could be himself or be anonymous; he could just be. When he was away from the keyboard, he used humor and music to disarm people, specifically early 1990s R&B which he loved singing; it helped him express himself.

One of his favorites was Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men’s One Sweet Day, especially the key change, the one on the last bridge with Mimi’s riffs, extra thick vibrato on the ‘ands’, melismas with a stank face. He’d switch octaves singing both Mariah and Boyz II Men, switching from falsetto to bass on a dime. I remember his rendition as somehow both beautiful and gut-wrenchingly hilarious; this was the genius of Khalid’s humor. Mariah wrote that song as a eulogy for her friend and collaborator David Cole, one half of C + C Music Factory, who died in 1995 from complications due to AIDS. (Khalid also had a notorious beatbox routine for EVERYBODY DANCE NOW.)

Whenever I listen to One Sweet Day, I hear Khalid, but it doesn’t make me think of just one specific moment, it’s more of a blur, of all the times I’ve heard him sing it over the years. Songs can help trigger memories of shared listening moments that stay with us on extended repeat.

Less than a year before Khalid’s murder, in 2015, the racist neighbor ran over Khalid’s mother, Haifa, with his car at full speed, which left her hospitalized and with injuries that she’s still rehabilitating. Reportedly, the police had allowed the man to finish chugging his beer next to the bloodied car before he was apprehended. Despite having prior felonies, he was repeatedly shown leniency. The ongoing American epidemic of the white male murderer is propped up systemically. During the bond hearing, the Tulsa County District Judge (and former Mayor) Bill LaFortune initially granted the neighbor bail of only $30,000. Only after strong rejections by the family did the judge reluctantly raise it to a mere $60,000. There are BLM protesters that have had higher bail set for simply disturbing the peace. Even more infuriating was the fact that the neighbor was allowed to move back next door with the simple promise that he would eventually relocate;. There were no requirements for an ankle monitor, no drug/alcohol testing; basically unconditional freedom. A few months later, Khalid found out the neighbor had gotten a hold of a gun. He called 911 twice to no avail, called his mother to tell her not to come home, and was shot dead, while on the phone.

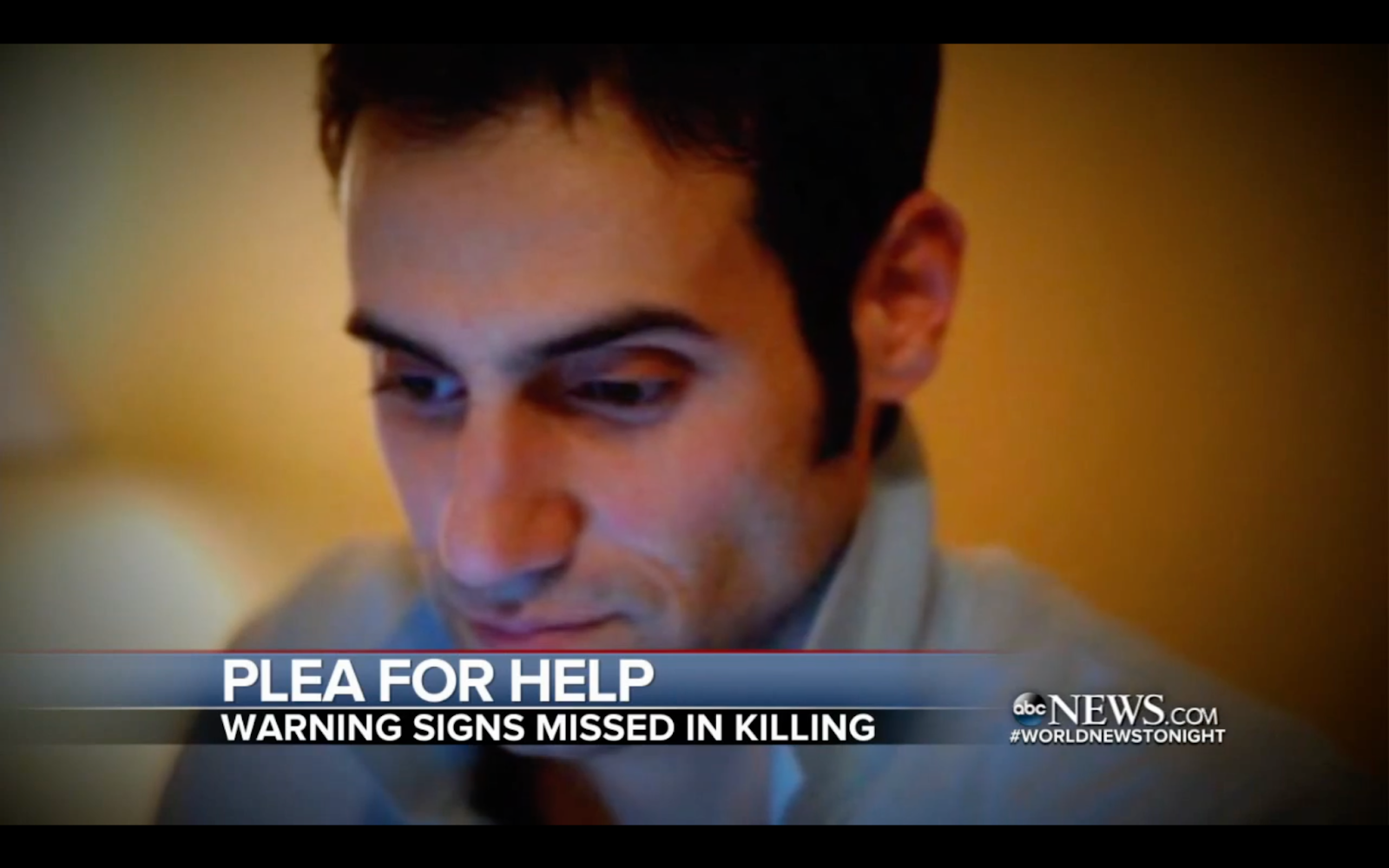

Negligence, egregious errors by local law enforcement, and gross failures by the state were all culpable accomplices. The tragedy was reported by all major international news media outlets, with headlines like “Son Killed by Neighbor who called him ‘Dirty Arab’” and “Did the System Fail Them?”.

Two of the images that were widely used in reporting on the tragedy were photos I had taken of Khalid while testing out a new camera lens over Christmas break the year before. Khalid was a year younger than me, also a middle child of three. We were friends by default growing up but ended up connecting on so many levels; we were blood. His image is my image. I revisit my photos of him often. Recently, maybe as a way to process my rage, I’ve started drawing them. I sit with Khalid’s image.

Trauma-informed care acknowledges that no matter where we turn, there are reminders all around us. The trauma of systemic violence, like the kind that led to Khalid’s death, is constantly being triggered with every subsequent act of racial violence, state violence, gun violence. Every hate-filled speech Trump riled on emboldened toxic behavior and normalized crazy. And this extends even beyond the borders of the US, to Beirut amidst the troubles, to all the places I carry inside me, and to all the places influenced by US criminal justice, diplomacy, and militarized police tactics.

These kinds of abuse tactics can take many forms, from outright violence, to creating conditions where accountability is not possible. Despite the high publicity surrounding the tragedy, Khalid’s murder went unreported in the Federal database for hate crimes. A glaring omission, negligence as a form of brutality, part and parcel of a problem that extends far beyond a count, to the families and communities these absent numbers impact. The Jabara family has gone on to tirelessly campaign for bond reform, victim rights, and accountability, helping to establish the Khalid Jabara and Heather Heyer National Opposition to Hate, Assault, and Threats to Equality Act (Jabara-Heyer NO HATE Act), a reform bill meant to address this disparity in hate crime data collection. It was introduced to US congress in 2019 but was never passed, and as I write this, is being reintroduced in light of the recent massacre in Atlanta and rising incidents of anti-Asian racism.

A lot of the other songs Khalid loved singing–Bone Thugs and Harmony’s Tha Crossroads, Faith Evans and Puff Daddy’s I’ll Be Missing You–were also eulogies. For some reason, it was a whole vibe back then. Pop songs on mourning were leading the charts in the ‘90s, across all genres of music. One Sweet Day topped the Billboard charts for a record-breaking sixteen consecutive weeks, an accomplishment that wouldn’t be surpassed for over 2 decades, that’s how popular it was. There is no equivalent song of mourning capturing so much of our attention, now, when we need it most.

When I see the photos below, when I draw them as a way of reclamation, I can’t help but think of these songs.

All that I remember of this photo is now tangled with the news reports that used this image.

Screenshots taken from news clips reporting on Khalid’s tragedy. To focus on the headlines, the photos are muted.

To unmute this image, to allow for the complexities and emotions to shine through beyond a single sensationalized headline.

How can we immutably embed the context, care, and love that goes into each photo. Is there a space to include this as a kind of emotional metadata?

Joe Namy is an artist, educator, and composer that often works collaboratively across mediums, in sound, performance, sculpture, and video, focusing on the social and political constructs of music and sound.